Core Stack Developer Overview¶

The ROS 2 core software stack breaks down into a few discrete but related parts:

When reading this document, references to an “interface” or an “API” generally imply a set of C or C++ headers which are installed, public, and subject to change control.

Also, when references to an “implementation” are made that generally implies a set of source files, e.g. .c or .cpp files, that implement one of the described APIs.

Build System¶

Under everything is the build system.

Iterating on catkin from ROS 1 we have created a set of packages under the moniker ament.

Some of the reasons for changing the name to ament are that we wanted it to not collide with catkin (in case we want mix them at some point) and to prevent confusion with existing catkin documentation.

ament’s primary responsibility is to make it easier to develop and maintain ROS 2 core packages.

However, this responsibility extends to any user who is willing to make use of our build system conventions and tools.

Additionally it should make packages conventional, such that developers should be able to pick up any ament based package and make some assumptions about how it works, how to introspect it, and how to build or use it.

ament consists of a few important repositories which are all in the ament GitHub organization:

The ament_package Package¶

Located on GitHub at ament/ament_package, this repository contains a single ament Python package which provides a Python API for finding and parsing package.xml files.

All ament packages must contain a single package.xml file at the root of the package regardless of their underlying build system. The package.xml “manifest” file contains information that is required in order to process and operate on a package. This package information includes things like the package’s name, which is globally unique, and the package’s dependencies. The package.xml file also serves as the marker file which indicates the location of the package on the file system.

Other than parsing the package.xml files, ament_package provides functionality to locate packages by searching the file system for these package.xml files.

- package.xml

- Package manifest file which marks the root of a package and contains meta information about the package including its name, version, description, maintainer, license, dependencies, and more. The contents of the manifest are in machine readable XML format and the contents are described in the REPs 127 and 140, with the possibility of further modifications in future REPs.

So anytime some package is referred to as an ament package, it means that it is a single unit of software (source code, build files, tests, documentation, and other resources) which is described using a package.xml manifest file.

- ament package

- Any package which contains a package.xml and follows the packaging guidelines of

ament, regardless of the underlying build system.

Since the term ament package is build system agnostic, there can be different kinds of ament packages, e.g. ament CMake package, ament Python package, etc.

Here is a list of common package types that you might run into in this software stack:

- CMake package

- Any package containing a plain CMake project and a package.xml manifest file.

- ament CMake package

- A CMake package that also follows the

amentpackaging guidelines. - Python package

- Any package containing a setuptools based Python project and a package.xml manifest file.

- ament Python package

- A Python package that also follows the

amentpackaging guidelines.

The ament_cmake Repository¶

Located on GitHub at ament/ament_cmake, this repository contains many “ament CMake” and pure CMake packages which provide the infrastructure in CMake that is required to create “ament CMake” packages.

In this context “ament CMake” packages means: ament packages that are built using CMake.

So the packages in this repository provide the necessary CMake functions/macros and CMake Modules to facilitate creating more “ament CMake” (or ament_cmake) packages.

Packages of this type are identified with the <build_type>ament_cmake</build_type> tag in the <export> tag of the package.xml file.

The packages in this repository are extremely modular, but there is a single “bottleneck” package called ament_cmake.

Anyone can depend on the ament_cmake package to get all of the aggregate functionality of the packages in this repository.

Here a list of the packages in the repository along with a short description:

ament_cmake- aggregates all other packages in this repository, users need only to depend on this.

ament_cmake_auto- provides convenience CMake functions which automatically handle a lot of the tedious parts of writing a package’s

CMakeLists.txtfile

- provides convenience CMake functions which automatically handle a lot of the tedious parts of writing a package’s

ament_cmake_core- provides all built-in core concepts for

ament, e.g. environment hooks, resource indexing, symbolic linking install and others

- provides all built-in core concepts for

ament_cmake_gmock- adds convenience functions for making gmock based unit tests

ament_cmake_gtest- adds convenience functions for making gtest based automated tests

ament_cmake_nose- adds convenience functions for making nosetests based python automated tests

ament_cmake_python- provides CMake functions for packages that contain Python code

ament_cmake_test- aggregates different kinds of tests, e.g. gtest and nosetests, under a single target using CTest

The ament_cmake_core package contains a lot of the CMake infrastructure that makes it possible to cleanly pass information between packages using conventional interfaces.

This makes the packages have more decoupled build interfaces with other packages, promoting their reuse and encouraging conventions in the build systems of different packages.

For instance it provides a standard way to pass include directories, libraries, definitions, and dependencies between packages so that consumers of this information can access this information in a conventional way.

The ament_cmake_core package also provides features of the ament build system like symbolic link installation, which allows you to symbolically link files from either the source space or the build space into the install space rather than copying them.

This allows you to install once and then edit non-generated resources like Python code and configuration files without having to rerun the install step for them to take effect.

This feature essentially replaces the “devel space” from catkin because it has most of the advantages with few of the complications or drawbacks.

Another feature provided by ament_cmake_core is the package resource indexing which is a way for packages to indicate that they contain a resource of some type.

The design of this feature makes it much more efficient to answer simple questions like what packages are in this prefix (e.g. /usr/local) because it only requires that you list the files in a single possible location under that prefix.

You can read more about this feature in the design docs for the resource index.

Like catkin, ament_cmake_core also provides environment setup files and package specific environment hooks.

The environment setup files, often named something like setup.bash, are a place for package developers to define changes to the environment that are needed to utilize their package.

The developers are able to do this using an “environment hook” which is basically an arbitrary bit of shell code that can set or modify environment variables, define shell functions, setup auto-completion rules, etc…

This feature is how, for example, ROS 1 set the ROS_DISTRO environment variable without catkin knowing anything about the ROS distribution.

The ament_python Repository¶

Located on GitHub at ament/ament_python, this repository contains several functions useful to set up and install python packages with ament-specific functionality.

The ament_lint Repository¶

Located on GitHub at ament/ament_lint, this repository provides several packages which provide linting and testing services in a convenient and consistent manner.

Currently there are packages to support C++ style linting using uncrustify, static C++ code checks using cppcheck, checking for copyright in source code, Python style linting using pep8, and other things.

The list of helper packages will likely grow in the future.

The ament_tools Package¶

Located on GitHub at ament/ament_tools, this repository provides a single ament Python package which provides command line tools for working with ament packages.

Like catkin_tools it provides a lot of its functionality in the ament build command, which can build a workspace of ament packages together at once.

Because ament_tools and ament_package are ament Python packages, they can be bootstrapped in an ament workspace just like any other package.

Ideally these tools could be combined with the tools provided by catkin_tools in order to provide a single tool for both build systems. We believe this is possible because the two build systems are so similar, but there has not been time to solve the remaining issues and actually consolidate the tools yet.

Internal ROS Interfaces¶

The internal ROS interfaces are public C APIs that are intended for use by developers who are creating client libraries or adding a new underlying middleware, but are not intended for use by typical ROS users. The ROS client libraries provide the user facing APIs that most ROS users are familiar with, and may come in a variety of programming languages.

Internal API Architecture Overview¶

There are two main internal interfaces:

The rmw API is the interface between the ROS 2 software stack and the underlying middleware implementation.

The underlying middleware used for ROS 2 is either a DDS or RTPS implementation, and is responsible for discovery, publish and subscribe mechanics, request-reply mechanics for services, and serialization of message types.

The rcl API is a slightly higher level API which is used to implement the client libraries and does not touch the middleware implementation directly, but rather does so through the ROS middleware interface (rmw API) abstraction.

As the diagram shows, these APIs are stacked such that the typical ROS user will use the client library API, e.g. rclcpp, to implement their code (executable or library).

The implementation of the client libraries, e.g. rclcpp, use the rcl interface which provides access to the ROS graph and graph events.

The rcl implementation in turn uses the rmw API to access the ROS graph.

The purpose of the rcl implementation is to provide a common implementation for more complex ROS concepts and utilities that may be used by various client libraries, while remaining agnostic to the underlying middleware being used.

The purpose of the rmw interface is to capture the absolute minimum middleware functionality needed to support ROS’s client libraries.

Finally, the implementation of the rmw API is provided by a middleware implementation specific package, e.g. rmw_fastrtps_cpp, the library of which is compiled against vendor specific DDS interfaces and types.

In the diagram above there is also a box labeled ros_to_dds, and the purpose of this box is to represent a category of possible packages which all the user to access DDS vendor specific objects and settings using the ROS equivalents.

One of the goals of this abstraction interface is to completely insulate the ROS user space code from the middleware being used, so that changing DDS vendors or even middleware technology has a minimal impact on the users code.

However, we recognize that on occasion it is useful to reach into the implementation and manually adjust settings despite the consequences that might have.

By requiring the use of one of these packages in order to access the underlying DDS vendor’s objects, we can avoid exposing vendor specific symbols and headers in the normal interface.

It also makes it easy to see what code is potentially violating the vendor portability by inspecting the package’s dependencies to see if one of these ros_to_dds packages are being used.

Type Specific Interfaces¶

All along the way there are some parts of the APIs that are necessarily specific to the message types being exchanged, e.g. publishing a message or subscribing to a topic, and therefore require generated code for each message type.

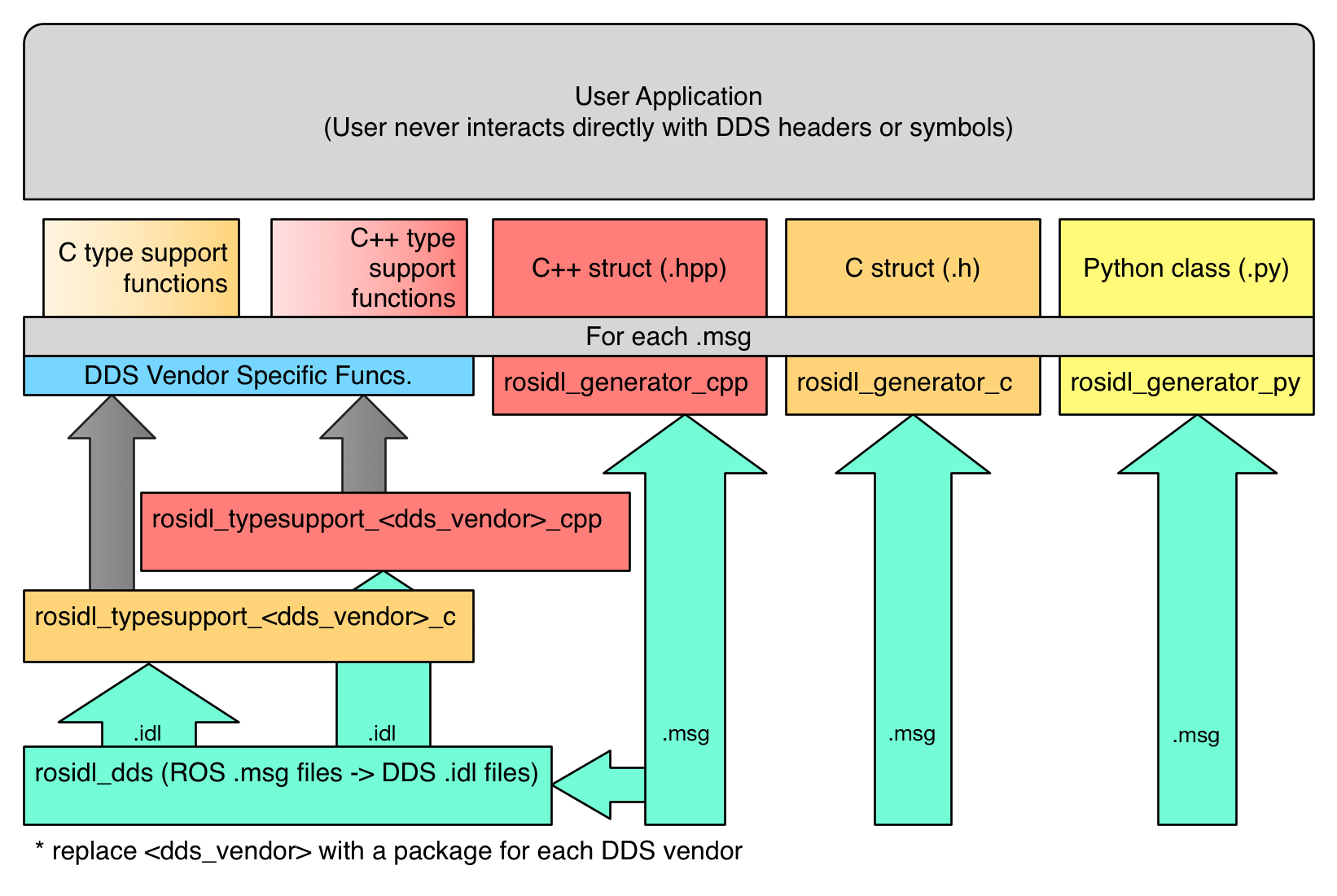

The following diagram layouts the path from user defined rosidl files, e.g. .msg files, to the type specific code used by the user and system to perform type specific functions:

Figure: flow chart of “static” type support generation, from rosidl files to user facing code.

The right hand side of the diagram shows how the .msg files are passed directly to language specific code generators, e.g. rosidl_generator_cpp or rosidl_generator_py.

These generators are responsible for creating the code that the user will include (or import) and use as the in-memory representation of the messages that were defined in the .msg files.

For example, consider the message std_msgs/String, a user might use this file in C++ with the statement #include <std_msgs/msg/string.hpp>, or they might use the statement from std_msgs.msg import String in Python.

These statements work because of the files generated by these language specific (but middleware agnostic) generator packages.

Separately, the .msg files are used to generate type support code for each type.

In this context, type support means: meta data or functions that are specific to a given type and that are used by the system to perform particular tasks for the given type.

The type support for a given message might include things like a list of the names and types for each field in the message.

It might also contain a reference to code that can perform particular tasks for that type, e.g. publish a message.

Static Type Support¶

When the type support references code to do particular functions for a specific message type, that code sometimes needs to do middleware specific work.

For example, consider the type specific publish function, when using “vendor A” the function will need to call some of “vendor A“‘s API, but when using “vendor B” it will need to call “vendor B“‘s API.

To allow for middleware vendor specific code, the user defined .msg files may result in the generation of vendor specific code.

This vendor specific code is still hidden from the user through the type support abstraction, which is similar to how the “Private Implementation” (or Pimpl) pattern works.

Static Type Support with DDS¶

For middleware vendors based on DDS, and specifically those which generate code based on the OMG IDL files (.idl files), the user defined rosidl files (.msg files) are converted into equivalent OMG IDL files (.idl files).

From these OMG IDL files, vendor specific code is created and then used within the type specific functions which are referenced by the type support for a given type.

The above diagram shows this on the left hand side, where the .msg files are consumed by the rosidl_dds package to produce .idl files, and then those .idl files are given to language specific and DDS vendor specific type support generation packages.

For example, consider the Connext DDS implementation, it has a package called rosidl_typesupport_connext_cpp.

This package is responsible for generating code to handle do things like publish to a topic for the C++ version of a given message type, using the .idl files generated by the rosidl_dds package to do so.

Again, this code, while specific to Connext, is still not exposed to the user because of the abstraction in the type support.

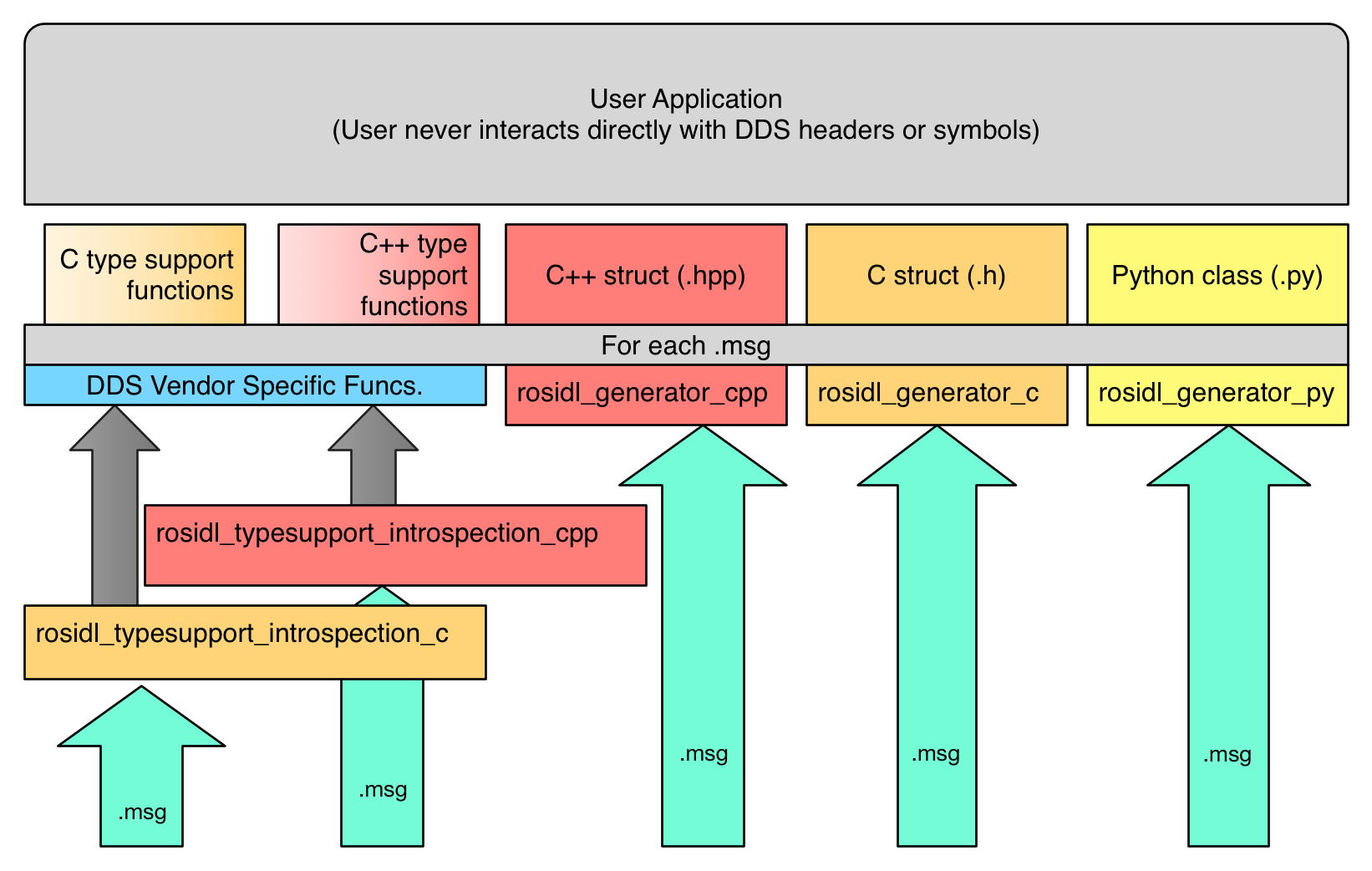

Dynamic Type Support¶

Another way to implement type support is to have generic functions for things like publishing to a topic, rather than generating a version of the function for each message type. In order to accomplish this, this generic function needs some meta information about the message type being published, things like a list of field names and types in the order in which they appear in the message type. Then to publish a message, you call a generic publish function and pass a message to be published along with a structure which contains the necessary meta data about the message type. This is referred to as “dynamic” type support, as opposed to “static” type support which requires generated versions of a function for each type.

Figure: flow chart of “dynamic” type support generation, from rosidl files to user facing code.

The above diagram shows the flow from user defined rosidl files to generated user facing code.

It is very similar to the diagram for static type support, and differs only in how the type support is generated which is represented by the left hand side of the diagram.

In dynamic type support the .msg files are converted directly into user facing code.

This code is also middleware agnostic, because it only contains meta information about the messages.

The function to actually do the work, e.g. publishing to a topic, is generic to the message type and will make any necessary calls to the middleware specific APIs.

Note that rather than dds vendor specific packages providing the type support code, which is the case in static type support, this method has middleware agnostic package for each language, e.g. rosidl_typesupport_introspection_c and rosidl_typesupport_introspection_cpp.

The introspection part of the package name refers to the ability to introspect any message instance with the generated meta data for the message type.

This is the fundamental capability that allows for generic implementations of functions like “publish to a topic”.

This approach has the advantage that all generated code is middleware agnostic, which means it can be reused for different middleware implementations, so long as they allow for dynamic type support. It also results in less generated code, which reduces compile time and code size.

However, dynamic type support requires that the underlying middleware support a similar form of dynamic type support. In the case of DDS the DDS-XTypes standard allows for publishing of messages using meta information rather than generated code. DDS-XTypes, or something like it, is required in the underlying middleware in order to support dynamic type support. Also, this approach to type support is normally slower than the static type support alternative. The type specific generated code in static type support can be written to be more efficient as it does not need to iterate over the message type’s meta data to perform things like serialization.

The rcl Repository¶

The ROS Client Library interface (rcl API) can be used by client libraries (e.g. rclc, rclcpp, rclpy, etc.) in order to avoid duplicating logic and features.

By reusing the rcl API, client libraries can be smaller and more consistent with each other.

Some parts of the client library are intentionally left out of the rcl API because the language idiomatic method should be used to implement those parts of the system.

A good example of this is the execution model, which rcl does not address at all.

Instead the client library should provide a language idiomatic solution like pthreads in C, std::thread in C++11, and threading.Thread in Python.

Generally the rcl interface provides functions that are not specific to a language pattern and are not specific to a particular message type.

The rcl API is located in the ros2/rcl repository on GitHub and contains the interface as C headers.

The rcl C implementation is provided by the rcl package in the same repository.

This implementation avoids direct contact with the middleware by instead using the rmw and rosidl APIs.

For a complete definition of the rcl API, see the API documentation:

The rmw Repository¶

The ROS middleware interface (rmw API) is the minimal set of primitive middleware capabilities needed to build ROS on top.

Providers of different middleware implementations must implement this interface in order to support the entire ROS stack on top.

Currently all of the middleware implementations are for different DDS vendors.

The rmw API is located in the ros2/rmw repository.

The rmw package contains the C headers which define the interface, the implementation of which is provided by the various packages of rmw implementations for different DDS vendors.

The rosidl Repository¶

The rosidl API consists of a few message related static functions and types along with a definition of what code should be generated by messages in different languages.

The generated message code specified in the API will be language specific, but may or may not reuse generated code for other languages.

The generated message code specified in the API contains things like the message data structure, functions for construction, destruction, etc.

The API will also implement a way to get the type support structure for the message type, which is used when publishing or subscribing to a topic of that message type.

There are several repositories that play a role in the rosidl API and implementation.

The rosidl repository, located on GitHub at ros2/rosidl, defines the message IDL syntax, i.e. syntax of .msg files, .srv files, etc., and contains packages for parsing the files, for providing CMake infrastructure to generate code from the messages, for generating implementation agnostic code (headers and source files), and for establishing the default set of generators.

The repository contains these packages:

rosidl_cmake: provides CMake functions and CMake Modules for generating code fromrosidlfiles, e.g..msgfiles,.srvfiles, etc.rosidl_default_generators: defines the list of default generators which ensures that they are installed as dependencies, but other injected generators can also be used.rosidl_generator_c: provides tools to generate C header files (.h) forrosidlfiles.rosidl_generator_cpp: provides tools to generate C++ header files (.hpp) forrosidlfiles.rosidl_generator_py: provides tools to generate Python modules forrosidlfiles.rosidl_parser: provides Python API for parsingrosidlfiles.

Generators for other languages, e.g. rosidl_generator_java, are hosted externally (in different repositories) but would use the same mechanism that the above generators use to “register” themselves as a rosidl generator.

In addition to the aforementioned packages for parsing and generating headers for the rosidl files, the rosidl repository also contains packages concerned with “type support” for the message types defined in the files.

Type support refers to the ability to interpret and manipulate the information represented by ROS message instances of particular types (publishing the messages, for example).

Type support can either be provided by code that is generated at compile time or it can be done programmatically based on the contents of the rosidl file, e.g. the .msg or .srv file, and the data received, by introspecting the data.

In the case of the latter, where type support is done through runtime interpretation of the messages, the message code generated by ROS 2 can be agnostic to the rmw implementation.

The packages that provide this type support through introspection of the data are:

rosidl_typesupport_introspection_c: provides tools for generating C code for supportingrosidlmessage data types.rosidl_typesupport_introspection_cpp: provides tools for generating C++ code for supportingrosidlmessage data types.

In the case where type support is to be generated at compile time instead of being generated programmatically, a package specific to the rmw implementation will need to be used. This is because typically a particular rmw implementation will require data to be stored and manipulated in a manner that is specific to the DDS vendor in order for the DDS implementation to make use of it. See the Type Specific Interfaces section above for more details.

For more information on what exactly is in the rosidl API (static and generated) see this page:

Warning

TODO: link to definition of rosidl APIs

The rcutils Repository¶

ROS 2 C Utilities is a C API containing of macros, functions, and data structures used throughout the ROS 2 codebase.

The ROS C Utilities (rcutils API) contains macros, functions, and data structures for error handling, commandline argument parsing, and logging that are not specific to the client or middleware layers and can be shared by both.

The rcutils API and implementation are located in the ros2/rcutils repository on GitHub which contains the interface as C headers.

For a complete definition of the rcutils API, see the API documentation:

ROS Middleware Implementations¶

ROS middleware implementations are sets of packages that implement some of the internal ROS interfaces, e.g. the rmw, rcl, and rosidl APIs.

Common Packages for DDS Middleware Packages¶

All of the current ROS middleware implementations are based on full or partial DDS implementations. For example, there is a middleware implementation that uses RTI’s Connext DDS and an implementation which uses eProsima’s Fast-RTPS. Because of this, there are some shared packages amongst most DDS based middleware implementations.

In the ros2/rosidl_dds repository on GitHub, there is the following package:

rosidl_generator_dds_idl: provides tools to generate DDS.idlfiles fromrosidlfiles, e.g..msgfiles,.srvfiles, etc.

The rosidl_generator_dds_idl package generates a DDS .idl file for each rosidl file, e.g. .msg file, defined by packages containing messages.

Currently DDS based ROS middleware implementations make use of this generator’s output .idl files to generate pre-compiled type support that is vendor specific.

Structure of ROS Middleware Implementations¶

A ROS middleware implementation is typically made up of a few packages in a single repository:

<implementation_name>_cmake_module: contains CMake Module for discovering and exposing required dependenciesrmw_<implementation_name>_<language>: contains the implementation of thermwAPI in a particular language, typically C++rosidl_typesupport_<implementation_name>_<language>: contains tools to generate static type support code forrosidlfiles, tailored to the implementation in a particular language, typically C or C++

The <implementation_name>_cmake_module package contains any CMake Modules and functions needed to find the supporting dependencies for the middleware implementation.

In the case of connext_cmake_module it has CMake Modules for finding the RTI Connext implementation in different places on the system since it does not ship with a CMake Module itself.

Not all repositories will have a package like this, for example eProsima’s Fast-RTPS provides a CMake module and so no additional one is required.

The rmw_<implementation_name>_<language> package implements the rmw C API in a particular language.

The implementation itself can be C++, it just must expose the header’s symbols as extern "C" so that C applications can link against it.

The rosidl_typesupport_<implementation_name>_<language> package provides a generator which generates DDS code in a particular language.

This is done using the .idl files generated by the rosidl_generator_dds_idl package and the DDS IDL code generator provided by the DDS vendor.

It also generates code for converting ROS message structures to and from DDS message structures.

This generator is also responsible for creating a shared library for the message package it is being used in, which is specific to the messages in the message package and to the DDS vendor being used.

As mentioned above, the rosidl_typesupport_introspection_<language> may be used instead of a vendor specific type support package if an rmw implementation supports runtime interpretation of messages.

This ability to programmatically send and receive types over topics without generating code beforehand is achieved by supporting the DDS X-Types Dynamic Data standard.

As such, rmw implementations may provide support for the X-Types standard, and/or provide a package for type support generated at compile time specific to their DDS implementation.

As an example of an rmw implementation repository, the opensplice ROS middleware implementation lives on GitHub at ros2/rmw_opensplice and has these packages:

opensplice_cmake_modulermw_opensplice_cpprosidl_typesupport_opensplice_crosidl_typesupport_opensplice_cpp

In addition to the opensplice repository of packages, there is the connext implementation on GitHub at ros2/rmw_connext.

It contains mostly the same packages, but it additionally contains a package to support the type support introspection using the DDS X-Types standard.

The rmw implementation using FastRTPS is on GitHub at eProsima/ROS-RMW-Fast-RTPS-cpp.

As FastRTPS currently only supports the type support introspection, there is no vendor specific type support package in this repository.

To learn more about what is required to create a new middleware implementation for ROS see this page:

Warning

TODO: Link to more detailed middleware implementation docs and/or tutorial.

ROS Client Interfaces (Client Libraries)¶

ROS Client Interfaces, a.k.a. client libraries, are user facing interfaces which provide the high level functionality and are built on top of the rcl and rosidl APIs.

The rclcpp Package¶

The ROS Client Library for C++ (rclcpp) is the user facing, C++ idiomatic interface which provides all of the ROS client functionality like creating nodes, publisher, and subscribers.

rclcpp builds on top of rcl and the rosidl API, and it is designed to be used with the C++ messages generated by rosidl_generator_cpp.

rclcpp makes use of all the features of C++ and C++11 to make the interface as easy to use as possible, but since it reuses the implementation in rcl it is able maintain a consistent behavior with the other client libraries that use the rcl API.

The rclcpp repository is located on GitHub at ros2/rclcpp and contains the package rclcpp.

The generated API documentation is here:

The rclpy Repositories¶

The ROS Client Library for Python (rclpy) is the Python counterpart to the C++ client library.

Like the C++ client library, rclpy also builds on top of the rcl C API for its implementation.

The interface provides an idiomatic Python experience which uses native Python types and patterns like lists and context objects, but by using the rcl API in the implementation it stays consistent with the other client libraries in terms of feature parity and behavior.

In addition to providing Python idiomatic bindings around the rcl API and Python classes for each message, the Python client library takes care of the execution model, using threading.Thread or similar to run the functions in the rcl API.

Like C++ it generates custom Python code for each ROS message that the user interacts with, but unlike C++ it eventually converts the native Python message object into the C version of the message.

All operations happen on the Python version of the messages until they need to be passed into the rcl layer, at which point they are converted into the plain C version of the message so it can be passed into the rcl C API.

This is avoided if possible when communicating between publishers and subscribers in the same process to cut down on the conversion into and out of Python.

The rclpy repository is located on GitHub at ros2/rclpy and contains the package rclpy.

Warning

TODO: Link to the rclpy API docs.